This post will comprise the second part on all things arctic (all things Svalbard) and follows the previous post on the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (and its resemblance to Echo Base from Star Wars).

Universitetssenteret på Svalbard

When certain institutions join JSTOR, you feel almost compelled to learn more about them. And this institution certainly grabbed my attention. This post takes us back to Svalbard, home of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, to investigate the Universitetssenteret på Svalbard, aka The University Centre in Svalbard, aka UNIS.

UNIS is without a doubt an intriguing case for the superlative award for higher education (as in the northernmost…). According to the website for UNIS:

“The University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) is the world’s northernmost higher education institution, located in Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen at 78°N. UNIS offers high quality courses at the undergraduate, graduate and postgraduate level in Arctic Biology, Arctic Geology, Arctic Geophysics and Arctic Technology.”

The world’s northernmost higher education institution? That text doesn’t do it justice nor does the abstraction of the 78th parallel. Svalbard is north, alright. Just a lot further north than many can imagine.

Being so far north, UNIS wisely concentrates on studies directly related to its preservation, such as Arctic Biology, Geology, Geophysics, and Arctic Technology. The research is equally focused on marine biology (Climate Effects on food quality in Arctic Marginal Ice Zones), arctic biology (invertebrate biogeography of Svalbard), and arctic geophysics (polarization of the oxygen thermospheric red line in Svalbard). To learn more about a heady lineup of research going on at UNIS, see their research page.

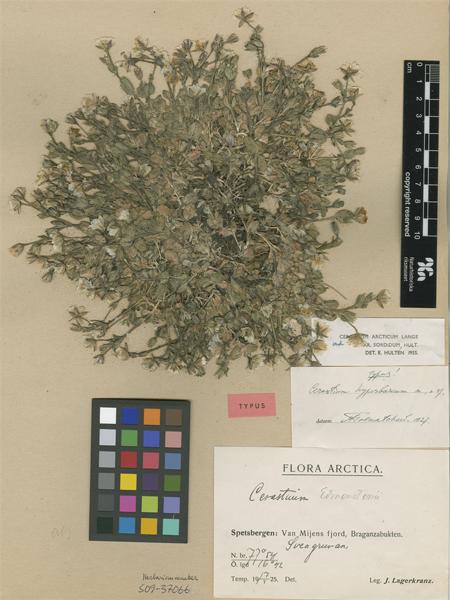

Surprisingly, quite a bit of plant life exists in the Arctic Circle (hence all the insects and animals feeding off it), mostly mosses, shrubs, and smaller plants. There aren’t any trees in the Arctic, but shrubs can get as high as a human. A lot of lichens and other plants grow here as well, including the one below. These plants support many of the herbivores residing in the Arctic Circle, including the hares, lemmings, muskox, and caribou. These animals in turn support predators such as foxes and wolves (and polar bears, although they prefer fish).

All in all, that makes for a fairly heady ecosystem taking place in an area that might at first glance might seem inhospitable to life in general. But with increasing demand for natural resources (the Arctic has that aplenty) and approximately 1/5 of the world’s water supply, I suspect that the Arctic in general will receive a lot more attention in the coming years and decades and not all for the better. This makes the kind of research happening at UNIS all the more important.

Clik here to view.

Cerastium hyperboreum Tolm from Svalbard contributed by the great people at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Phanerogamic Botany

In case you wanted to get apply to UNIS and explore the arctic environment, consider that of the 350 students currently attending, 50% are Norwegian and 50% are international. English is the language of instruction so don’t let your lack of Norse deter you. The frozen tundra awaits. This webcam casting out into the vast harbor certainly speaks to the imagination.

Longyearbyen

Longyearbyen is the largest city in the Svalbard archipelago with around 2000 inhabitants and is the world’s most northerly town with a population over 1000. Svalbard itself was discovered by the Dutch in the late 16th century, but wasn’t actually considered a part of any particular country until the Treaty of Versailles made it officially part of Norway. It has been to quite a bit of mining activity over the years, with American, British, Swedish, Russian, German, and Norwegian interests there (Sommers, 1952).

Longyearbyen also experiences a polar night that lasts from October through to early March and a polar day lasts from April through to the end of August. Perpetual darkness or perpetual sunlight. They go the distance on Svalbard; no half measures here.

Also quite unique about Longyearbyen and the surrounding Svalbard is that due to the permafrost (the same permafrost that drew the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in the first place), one cannot be buried there after death. It was discovered about 70 years ago that bodies were failing to decompose due to the cold. Anyone who dies on Longyearbyen is flown to the Norwegian mainland for burial.

Scientifically, it is there preserved bodies that are attracting interest. The Flu Pandemic of 1918, aka the Spanish Flu (immediately after and during the First World War) killed an estimated 50 million people, or 3% of the world’s population at the time. Some of the preserved bodies on Svalbard succumbed to this flu and so scientists believe they can study and/or recreate the nasty strain of this virus by extracting it from these bodies.

But rather than hang that morbid anectdote on the shoulders of sturdy Svalbard, I will leave you with a capture of a webcam staring out into the harbor at Longyearbyen. That is impressive.

Clik here to view.

A webcam image of Svalbard Harbor taken on 7.14.2010. Click the image to go to the live webcam.

To learn more, see these articles in JSTOR for further research ideas:

Johnson, J. et al (2005). Cumulative Effects of Human Developments on Arctic Wildlife. Wildlife Monographs, 160 (Jul., 2005): pp. 1-36

Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3830812

Callaghan, T. et al (2004). Biodiversity, Distributions and Adaptations of Arctic Species in the Context of Environmental Change. Ambio, 33 ( 7): pp. 404-417. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4315523

Cooper, E. (2004). Plant Recruitment in the High Arctic: Seed Bank and Seedling Emergence on Svalbard. Journal of Vegetation Science, 15 (1) : pp. 115-124. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3236502.

Hobbs, William (1949). Zeno and the Cartography of Greenland. Imago Mundi, 6, (1949): pp. 15-19. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1149972

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Clik here to view.